An Urdu collection of fatawa of the late Indian master jurist and qazi, Mujahid al-Islam al-Qasimi. He is the founder of the Majma’ al-Fiqh al-Islami fi ‘l-Hind, or the Islamic Fiqh Academy of India. Fatawa Qazi

Category Archives: Fiqh

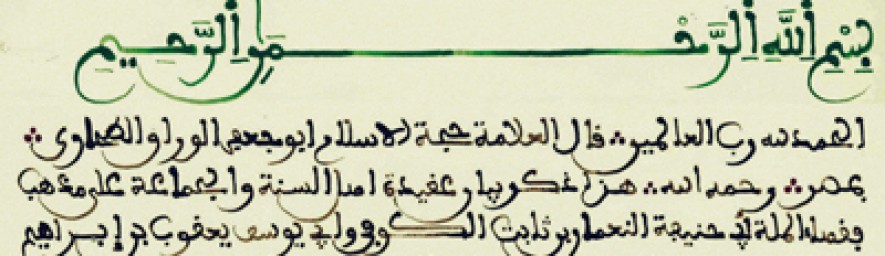

Maqalat al-Kawthari of ‘Allamah Muhammad Zahid al-Kawthari

A must-read for any serious student of knowledge: Maqalat al-Kawthari

Translation of the Chapter on Raf’ al-Yadayn from I’la’ al-Sunan

Chapter on Not Raising the Hands in other than the Opening & the Command to be Still in Salah By ‘Allamah Zafar Ahmad al-‘Uthmani Translated by Zameelur Rahman 1. Narrated from Tamim ibn Tarafah from Jabir ibn Samurah (Allah be pleased with him): He said: Allah‟s Messenger (Allah bless him and grant him peace) cameContinueContinue reading “Translation of the Chapter on Raf’ al-Yadayn from I’la’ al-Sunan”

Translation of the Introduction to I’la’ al-Sunan by Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani

This wonderful introduction succinctly discusses the biographies of Imam Ashraf ‘Ali al-Thanawi and Imam Zafar Ahmad al-Thanawi as well as an introduction to the renowned work: I’la’ al-Sunan. The translation has been done by our dear friend and regular contributor, Zameelur Rahman, along with a translation of a chapter of the book that will beContinueContinue reading “Translation of the Introduction to I’la’ al-Sunan by Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani”

Translation of Mawlana Habib Ahmad al-Kiranawi’s Al-Din al-Qayyim, Part of the Introduction to I’la’ al-Sunan

at-Tahawi.com is pleased to announce the online release of Mawlana Habib Ahmad al-Kiranawi’s al-Din al-Qayyim, a treatise on taqlid and ijtihad and a detailed refutation of Imam Ibn al-Qayyim’s views on taqlid. The treatise is included in the introduction to Imam Zafar Ahmad al-‘Uthmani’s monumental and renowned work, I’la’ al-Sunan, a collection of over six thousand hadith proofsContinueContinue reading “Translation of Mawlana Habib Ahmad al-Kiranawi’s Al-Din al-Qayyim, Part of the Introduction to I’la’ al-Sunan”

Simplified Fiqhi Encyclopedia

Here one can read and download the “Simplified Fiqhi Encylopedia” by dr. Magda Amer in English: http://islam-inpractice.com/downloads/Simplified_Fiqhi_Encylopedia.pdf This is a work of comparative fiqh in questions and answers format. Dr. Magda Amer is a female Islamic scholar in religious and worldly sciences.