asSalaamu Alaikum, [This book can be obtained from Manak Publications, New Delhi and Maktaba Darul Uloom Deoband by emailing them at info@darululoom-deoband.com] UPDATE: The PDF file of this book is available for download here. Darul Uloom Deoband published the English version of Silk Letter Movement compiled by Hadhrat Maulana Muhammad Miyan Deobandi. The bookContinueContinue reading “Darul Uloom Publishes English Version of ‘Silk Letter Movement’ – 2/18/13”

Category Archives: Book Reviews

NEW BOOK RELEASE: “Shaykh ’Abū al-Hasan ‘Alī Nadwī – His Life & Works” by Shaykh Mohammad Akram Nadwi

asSalaamu Alaikum, Author: Shaykh Mohammad Akram Nadwi Format: Paperback Pages: 314 ISBN: 978-0957402904 Sample Pages About The Book Shaykh ’Abū al-Hasan ‘Alī Nadwī (1914-1999/1332-1419 AH), one of the most widely read and influential scholars of our time, was likened by his intellectual peers to the exemplary scholars of the earliest generations of Islam. His writingsContinueContinue reading “NEW BOOK RELEASE: “Shaykh ’Abū al-Hasan ‘Alī Nadwī – His Life & Works” by Shaykh Mohammad Akram Nadwi”

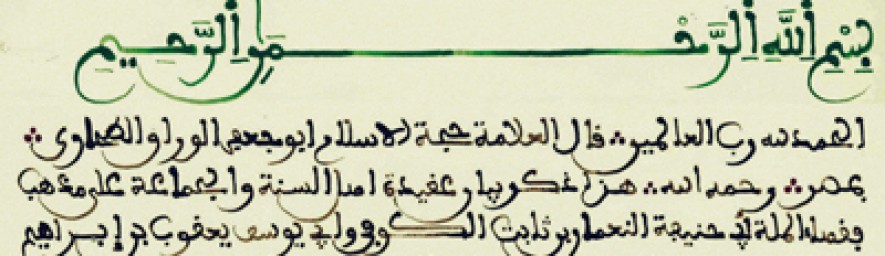

al-Hawi li ‘l-Fatawi li ‘l-Imam al-Suyuti

A book of fatawa by Imam Suyuti rahimahullah with many controversial and still relevant issues like mawlid, loud group dhikr, the hadra and the tasbih, to name a few, and much more; on almost each (still) controversial (in the sense of the debates between Salafis and Sufis to put it simply) topic one can thinkContinueContinue reading “al-Hawi li ‘l-Fatawi li ‘l-Imam al-Suyuti”

New Release: “The Inseparability Of Shari’a & Tariqa” by Shaykh Muhammad Zakariyya al-Kandhlawi

asSalaamu Alaikum, Over the past two years, Madania Publications has revamped their publishing by making the change to publish books with better material quality and style (glossy cover, better print, proper margins, less misprints, attractive cover images, etc.). This is very well appreciated as Islamic literature in the English language, usually translated works, often lacksContinueContinue reading “New Release: “The Inseparability Of Shari’a & Tariqa” by Shaykh Muhammad Zakariyya al-Kandhlawi”

Bastions of the Believers: Madrasahs and Islamic Education in India – Book Review

Book Review of Yoginder Sikand’s BASTIONS OF THE BELIEVERS: MADRASAHS AND ISLAMIC EDUCATION IN INDIA By ‘Aamir Bashir Madrasahs in the Indian Subcontinent suffer from a poor image. The mainstream media in the West, as well as in the sub-continent (especially Hindu and liberal), tends to brand the madrasahs as hotbeds of terrorism and breedingContinueContinue reading “Bastions of the Believers: Madrasahs and Islamic Education in India – Book Review”

Versions of the book “al-Adhkar” of imam an-Nawawi

I have just received the book “al-Adkhar” by imam an-Nawawi from Dar al-Minhaj (http://www.alminhaj.com/) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. I bought it from HUbooks in the UK (http://www.hubooks.com/). Last year I got another copy of the same book from a bookseller in the Netherlands but from a different publisher: Dar al-Fajr li’t-Turath, which is behind al-AzharContinueContinue reading “Versions of the book “al-Adhkar” of imam an-Nawawi”